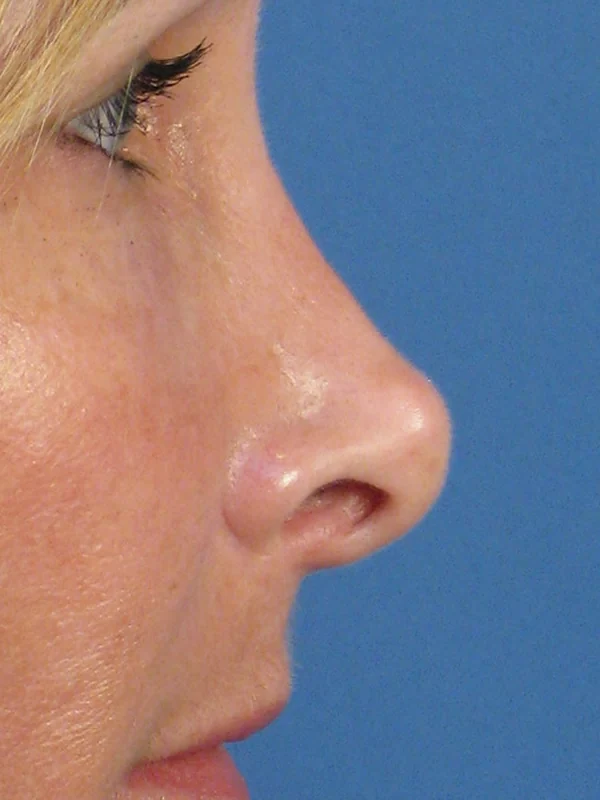

Composite ear grafts are used in rhinoplasty and revision rhinoplasty surgery primarily to adjust and reshape the nostril rim. More specifically, composite grafts are employed in cases where the nostril rim is excessively arched. For example, the adjacent photo shows an actual patient who presented to my office for revision rhinoplasty following prior cosmetic nose surgery performed by another plastic surgeon. As you can see, the inside of her nose is quite visible from this side view. This is due in part to the nostril rim being excessively arched. Rhinoplsty surgeons also frequently refer to this problem as alar retraction, referring to the alar rim being retracted or pulled upward.

Composite ear grafts are used in rhinoplasty and revision rhinoplasty surgery primarily to adjust and reshape the nostril rim. More specifically, composite grafts are employed in cases where the nostril rim is excessively arched. For example, the adjacent photo shows an actual patient who presented to my office for revision rhinoplasty following prior cosmetic nose surgery performed by another plastic surgeon. As you can see, the inside of her nose is quite visible from this side view. This is due in part to the nostril rim being excessively arched. Rhinoplsty surgeons also frequently refer to this problem as alar retraction, referring to the alar rim being retracted or pulled upward.

In rare cases, the appearance of alar retraction can be present congenitally in the absence of any history of prior nose surgery. However, much more commonly alar retraction is a result of prior rhinoplasty surgery.

So how does this type of problem occur? It is usually a consequence of aggressive resection of cartilage in the region of the lateral crus. But what is the lateral crus? As shown in the adjacent photo diagram, the lateral crus is the segment of cartilage located just below the skin and above the nostril opening. The lateral crus essentially provides the nostril with an underlying framework of support, which gives it the shape that you ultimately see. Ideally, this shape is a gentle arch that allows you to see into the nose only a few millimeters (termed ‘columellar show’ by us rhinoplasty surgeons). The adjacent photo example provided is actually the post-operative profile photo of a rhinoplasty patient of mine, which demonstrates a very natural nostril contour without any evidence of alar retraction.

So how does this type of problem occur? It is usually a consequence of aggressive resection of cartilage in the region of the lateral crus. But what is the lateral crus? As shown in the adjacent photo diagram, the lateral crus is the segment of cartilage located just below the skin and above the nostril opening. The lateral crus essentially provides the nostril with an underlying framework of support, which gives it the shape that you ultimately see. Ideally, this shape is a gentle arch that allows you to see into the nose only a few millimeters (termed ‘columellar show’ by us rhinoplasty surgeons). The adjacent photo example provided is actually the post-operative profile photo of a rhinoplasty patient of mine, which demonstrates a very natural nostril contour without any evidence of alar retraction.

A very common maneuver in rhinoplasty is called cephalic trimming, which refers to the act of cutting, or resecting, the cephalic margin of the lateral crus. The cephalic margin is the upper edge of the cartilage. This is frequently done to reduce unwanted fullness in this area of the nasal tip with the goal of creating a more defined and narrowed nasal tip. In many cases when this is done in a conservative manner (leaving behind an adequate amount of the lateral crus cartilage), the results can be very acceptable. Unfortunately, in cases where an overly aggressive amount of cartilage is resected during cephalic trimming of the lateral crus, alar retraction is much more likely to result. What typically happens in this scenario is shown in the diagram to the left. The red shaded area represents an overly aggressive cephalic trimming of the lateral crus cartilage. When this is done, only a relatively narrow segment of the lateral crus remains. As the healing process unfolds over many months, the effects of internal scarring begin to impact the remnant of the lateral crus. Scarring is important in this situation since because it essentially equates to pulling of the tissues in a certain direction.

A very common maneuver in rhinoplasty is called cephalic trimming, which refers to the act of cutting, or resecting, the cephalic margin of the lateral crus. The cephalic margin is the upper edge of the cartilage. This is frequently done to reduce unwanted fullness in this area of the nasal tip with the goal of creating a more defined and narrowed nasal tip. In many cases when this is done in a conservative manner (leaving behind an adequate amount of the lateral crus cartilage), the results can be very acceptable. Unfortunately, in cases where an overly aggressive amount of cartilage is resected during cephalic trimming of the lateral crus, alar retraction is much more likely to result. What typically happens in this scenario is shown in the diagram to the left. The red shaded area represents an overly aggressive cephalic trimming of the lateral crus cartilage. When this is done, only a relatively narrow segment of the lateral crus remains. As the healing process unfolds over many months, the effects of internal scarring begin to impact the remnant of the lateral crus. Scarring is important in this situation since because it essentially equates to pulling of the tissues in a certain direction.  This is usually from an area of instability to an area of more stability. If scarring occurred equally above and below the remaining lateral crus, there would really be no issues. Unfortunately, scarring does not occur below the lateral crus because there are no forces to pull in the direction of the nostril opening. The only force of scarring that occurs is on the side where the cartilage was removed. The green arrows in the adjacent photo diagram indicate the effects of this scarring on the lateral crus after aggressive cephalic trimming. The ‘pull’ from the scarring is directed upward toward the middle of the nose where the tissues are more stable (again, going from an area of instability to an area of stability). As this occurs, the lower lateral cartilage remnant will scar upward away from the nostril opening (see arched cartilage as shown to the right). The end result clinically is a nostril rim that begins to appear excessively arched upward, or retracted.

This is usually from an area of instability to an area of more stability. If scarring occurred equally above and below the remaining lateral crus, there would really be no issues. Unfortunately, scarring does not occur below the lateral crus because there are no forces to pull in the direction of the nostril opening. The only force of scarring that occurs is on the side where the cartilage was removed. The green arrows in the adjacent photo diagram indicate the effects of this scarring on the lateral crus after aggressive cephalic trimming. The ‘pull’ from the scarring is directed upward toward the middle of the nose where the tissues are more stable (again, going from an area of instability to an area of stability). As this occurs, the lower lateral cartilage remnant will scar upward away from the nostril opening (see arched cartilage as shown to the right). The end result clinically is a nostril rim that begins to appear excessively arched upward, or retracted.

In mild cases of alar retraction where the nostril rim has been pulled up, a procedure can be done using what is called an alar rim cartilage graft to help correct the deformity. In these cases, a relatively thin piece of cartilage can be taken from the septum (inside of the nose) or the ear and placed within a small pocket created on the inner lining of the nostril rim. In doing so, this can help give the illusion the nostril rim has been pulled down slightly.

In more severe cases of alar retraction, a different type of graft is required to make a more substantial change. We refer to this type of graft as a composite graft, or composite ear graft. It is termed a composite graft because it is comprised of not just cartilage but three different types of tissue. This includes skin, cartilage and perichondrium (soft tissue).

In more severe cases of alar retraction, a different type of graft is required to make a more substantial change. We refer to this type of graft as a composite graft, or composite ear graft. It is termed a composite graft because it is comprised of not just cartilage but three different types of tissue. This includes skin, cartilage and perichondrium (soft tissue).  A composite graft is typically harvested from an area of the ear called the concha cymba. This is shown in the adjacent photo as the purple outlined area. Harvesting the graft from this specific area provides the rhinoplasty surgeon a sufficiently large composite graft that can essentially span the entire length of the nostril opening (see an actual composite graft to the right). It also allows for great concealment of the harvest site and, therefore, minimal visible scarring of the ear. In fact, in many cases I don’t even put sutures in the ear to close this donor site. If left alone, the body will slowly fill in the defect, which includes formation of a new skin layer. In many cases, the end result looks much more natural when compared with those patients who had sutures placed in an attempt to close the site.

A composite graft is typically harvested from an area of the ear called the concha cymba. This is shown in the adjacent photo as the purple outlined area. Harvesting the graft from this specific area provides the rhinoplasty surgeon a sufficiently large composite graft that can essentially span the entire length of the nostril opening (see an actual composite graft to the right). It also allows for great concealment of the harvest site and, therefore, minimal visible scarring of the ear. In fact, in many cases I don’t even put sutures in the ear to close this donor site. If left alone, the body will slowly fill in the defect, which includes formation of a new skin layer. In many cases, the end result looks much more natural when compared with those patients who had sutures placed in an attempt to close the site.

In concept, the composite graft can be positioned along the inner lining of the nostril to help ‘pull’ the rim downward in an attempt to restore a more natural looking contour. This is shown diagrammatically in the adjacent photo where the green ellipse represents placement of a composite ear graft. Before the composite graft can be placed, an incision, or cut, has to be made along the inner surface of the nostril. This incision is then widened in a vertical direction, thus creating a precise pocket where the graft can be placed. The graft is positioned such that the skin is left facing into the nose. The skin layer is a really important component of the composite graft that helps to re-expand the contracted, or shrunken, inner lining of the nostril that results from alar retraction. The middle layer of the composite graft is made of cartilage, which provides the necessary rigidity to keep the nostril rim in its new, desired position. The deep perichondrium layer helps optimize blood supply to the graft while also providing for some degree of added internal cushioning.

In concept, the composite graft can be positioned along the inner lining of the nostril to help ‘pull’ the rim downward in an attempt to restore a more natural looking contour. This is shown diagrammatically in the adjacent photo where the green ellipse represents placement of a composite ear graft. Before the composite graft can be placed, an incision, or cut, has to be made along the inner surface of the nostril. This incision is then widened in a vertical direction, thus creating a precise pocket where the graft can be placed. The graft is positioned such that the skin is left facing into the nose. The skin layer is a really important component of the composite graft that helps to re-expand the contracted, or shrunken, inner lining of the nostril that results from alar retraction. The middle layer of the composite graft is made of cartilage, which provides the necessary rigidity to keep the nostril rim in its new, desired position. The deep perichondrium layer helps optimize blood supply to the graft while also providing for some degree of added internal cushioning.

So what does this look like in real life? The adjacent photo is an intraoperative view of what a real composite ear graft appears like going into the defect (left) and when finally positioned and sewn into the inner lining of the nostril (right). The skin layer of the composite graft is whiter than the surrounding, natural skin color because there is no blood circulating in the graft at this time. It will actually take hours to days before the composite graft has any significant amount of blood supply coming in to it from the surrounding nostril tissue. Fortunately, this occurs very predictably in most cases. As you can see, the height of the composite graft largely dictates how much the nostril rim can be brought down. So in cases where there is more severe alar retraction, a much larger composite graft is necessary to make more substantial, visible changes in nostril rim position.

So what does this look like in real life? The adjacent photo is an intraoperative view of what a real composite ear graft appears like going into the defect (left) and when finally positioned and sewn into the inner lining of the nostril (right). The skin layer of the composite graft is whiter than the surrounding, natural skin color because there is no blood circulating in the graft at this time. It will actually take hours to days before the composite graft has any significant amount of blood supply coming in to it from the surrounding nostril tissue. Fortunately, this occurs very predictably in most cases. As you can see, the height of the composite graft largely dictates how much the nostril rim can be brought down. So in cases where there is more severe alar retraction, a much larger composite graft is necessary to make more substantial, visible changes in nostril rim position.

Composite Ear Graft Photo Examples

Case Example 1

The first example below demonstrates a milder case of alar retraction. This particular female patient had prior surgery performed by another plastic surgeon. Unfortunately, changes were made to her nostril resulting in mild arching of the nostril contour. Like many patients who are candidates for a composite graft, this one disliked the fact you could see more of the inside of her nose – what we refer to as ‘excess nostril show’ in the world of rhinoplasty. I performed bilateral composite ear grafts with delicate placement along the inner surface of the nostril on both sides. As you can see from her before and after photos, the nostril rim has been brought down a few millimeters, which is all she really needed to provide a more natural looking contour. There is now less nostril show and unwanted arching as the alar retraction has been corrected.

Case Example 2

This second example of a composite ear graft shows a patient with more severe alar retraction. This female patient from San Diego underwent prior rhinoplasty by a different plastic surgeon. Unfortunately, she ended up with rather marked alar retraction after the lateral crus segment of cartilage was removed with over-aggressive surgical technique. As part of a more formal revision rhinoplasty procedure, I was able to place bilateral composite ear grafts to draw the nostril rim downward on both sides. The end result in terms of the nostrils, is a much more natural looking contour and position with minimal residual signs of unwanted alar retraction.

Composite Ear Graft Consult

If you have issues with alar retraction with excessively arched nostril rims, contact my San Diego office today to discuss options in terms of possible composite ear graft surgery.